Sedation is a key management priority of an ICU patient. It is especially important given the degree of organ support that some patients require and how uncomfortable and distressing this would be without sedation. Both under and over-sedation can have significant physiological consequences. In addition, a good sedation strategy can mitigate some of the psychological sequelae of critical illness.

Monitoring Sedation

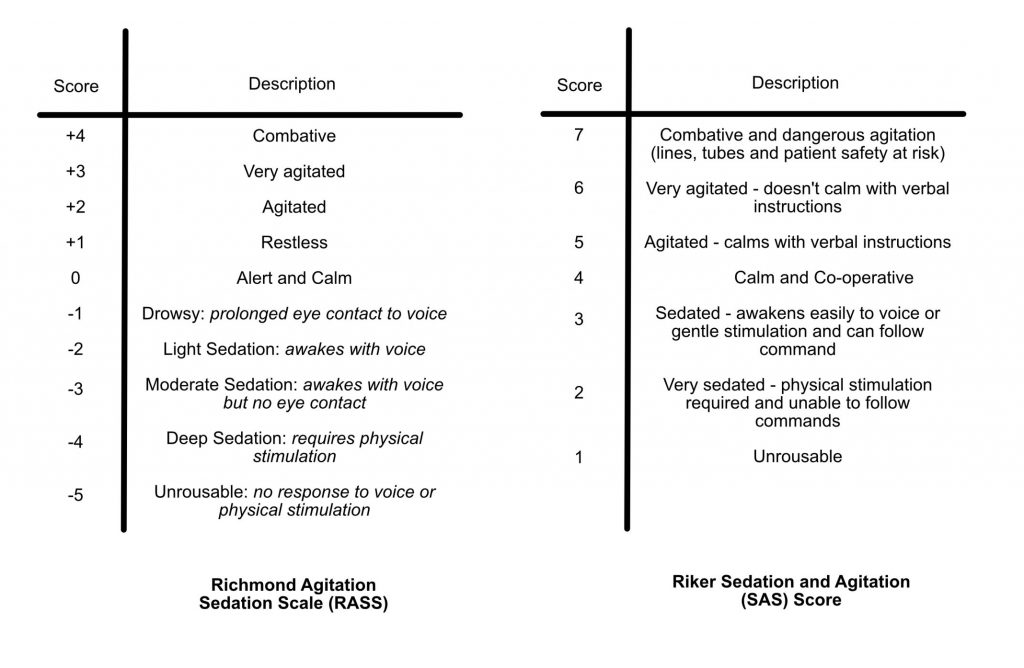

There are two common sedation scoring tools in use in ICU – the RASS and Riker score. Consultants may give targets to wean the sedation too. These two scores are detailed below:

Historically, ventilated ICU patients have required deep sedation and paralysis to tolerate invasive ventilation. However, with the advent of more advanced ventilatory modes sedation requirements are less, as ventilation in most patients is better tolerated.

Each patient will have a different sedation target depending on clinical course. However, for a stable patient that is requiring ventilation and relatively tolerant of their endotracheal tube a RIKER score of 3 – 4 and RASS of 0 – -2 would be appropriate. A sedation hold should be considered each day to allow for neurological assessment.

Sedative drugs in the ICU

This section will cover commonly used sedative drugs in ICU. It is not exhaustive and covers only the basics.

Propofol

- A white coloured hypnotic agent that possesses no analgesic properties. Works by potentiating effect of GABA-A channels. GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter.

- Onset in 30-60 seconds. Quick offset (minutes) due to redistribution into fat.

- Renal elimination of inactive metabolites.

- Dosing: Induction 1-2 mg/kg, Maintenance 4 – 12 mcg/kg/hr (clinically, infusion titrated to effect between 10 and 200mg/hr). Administered neat.

- Side Effects:

- CVS: Hypotension (needs to be used with significant caution in haemodynamically unstable patients), negative inotropy and bradycardia

- RESP: Apnoea, loss of airway reflexes

- METABOLIC: Propofol infusion syndrome, Hypertriglyceridemia (probably only clinically relevant if pancreatitis caused by high triglycerides)

- OTHER: pain on injection

Fentanyl

- A clear coloured synthetic opioid that binds to opioid receptors inhibiting transmission of pain. Multiple routes of administration exist.

- Rapid onset (faster than morphine due to increased fat solubility), and hepatically metabolised to inactive metabolites. Renal failure has less of an effect on duration of action (as the kidneys only eliminate inactive metabolites).

- Morphine is partially metabolised to more potent active metabolites that are renally excreted. In renal failure these can accumulate leading to increased adverse effects and toxicity.

- In prolonged infusion, due to its high lipid solubility, fat becomes saturated and can act as a reservoir of the drug which will continue to replenish plasma levels and increase duration of effect even once IV infusion ceased.

- Dosing: 10-20mcg boluses titrated to effect for analgesia, infusions tend to start at 20mcg/hr. Usually made up as 500 micrograms in 50mls normal saline.

- Side Effects:

- CVS: Hypotension (this is more common with morphine than fentanyl due to histamine release)

- RESP: Obtunded response to CO2 and decreased RR

- CNS: Sedation, euphoria, pupillary constriction (stimulates Edinger-Westphal Nucleus)

- GI: Nausea and vomiting, constipation

- MSK: Chest wall rigidity and pruritus

- Reversal:

- Naloxone: 100mcg boluses – may require infusion if multiple boluses required.

Midazolam

- A benzodiazepine that binds to GABA receptors and enhances their activity.

- Has sedative, hypnotic, and anxiolytic properties.

- Hepatically metabolised by P450 system to active metabolites. These can accumulate in renal failure and prolong effects and risk of toxicity.

- Highly lipid soluble – in long infusions can accumulate in fat and pharmacodynamic effects can be prolonged even following cessation of infusion (this is known as a prolonged context sensitive half time).

- Fastest clearance of all benzodiazepines which is why midazolam infusions are often used in critical care.

- Dosing: 0.5-1mg boluses, infusions titrated to effect – usually start at 1-2mg/hr. Usually made up as 50mg in 50mls normal saline.

- Side Effects:

- CVS: Often stable cardiac output, but can cause hypotension.

- RESP: Decreased RR, apnoea

- MSK: Skeletal muscle relaxation

- CNS: Potential increased risk of delirium

- Reversal: Flumazenil – rarely used due to risk of seizures

Dexmedetomidine

- Central alpha-2 agonist that is often used in weaning phase of mechanical ventilation

- Sedative and analgesic

- Hepatically metabolised to inactive metabolites

- Dosing: Infusion 0.2mcg/kg/hr to 1 mcg/kg/hr (can sometimes be higher). Usually made up as 400 micrograms in 100mls Normal Saline.

- Side Effects:

- CVS: Initially causes hypertension then prolonged hypotension and bradycardia. Rebound hypertension if abruptly ceased

- CNS: Anxiolysis, sedation and amnesia

Clonidine

- Alpha-2 agonist that can be given as a bolus (25-50 mcg TDS PO or IV) or run as an infusion. Similar side effects to dexmedetomidine.

Haloperidol

- Typical anti-psychotic used for behavioural emergencies. Also has use as anti-emetic in lower doses.

- Can be given IV, IM or orally

- Dosing: PO 5 – 10mg, IV 1 – 5mg boluses titrated to effect

- Side Effects:

- CVS: QTC prolongation

- CNS: Extra pyramidal side effects, Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (avoid in Parkinsonian patients)

References and Further Reading

NEJM Review article: Sedation and Delirium in ICU

British Journal of Anaesthesia Education: Sedation in ICU

Context Sensitive Half Time Definition

Author: George Walker