Terminology

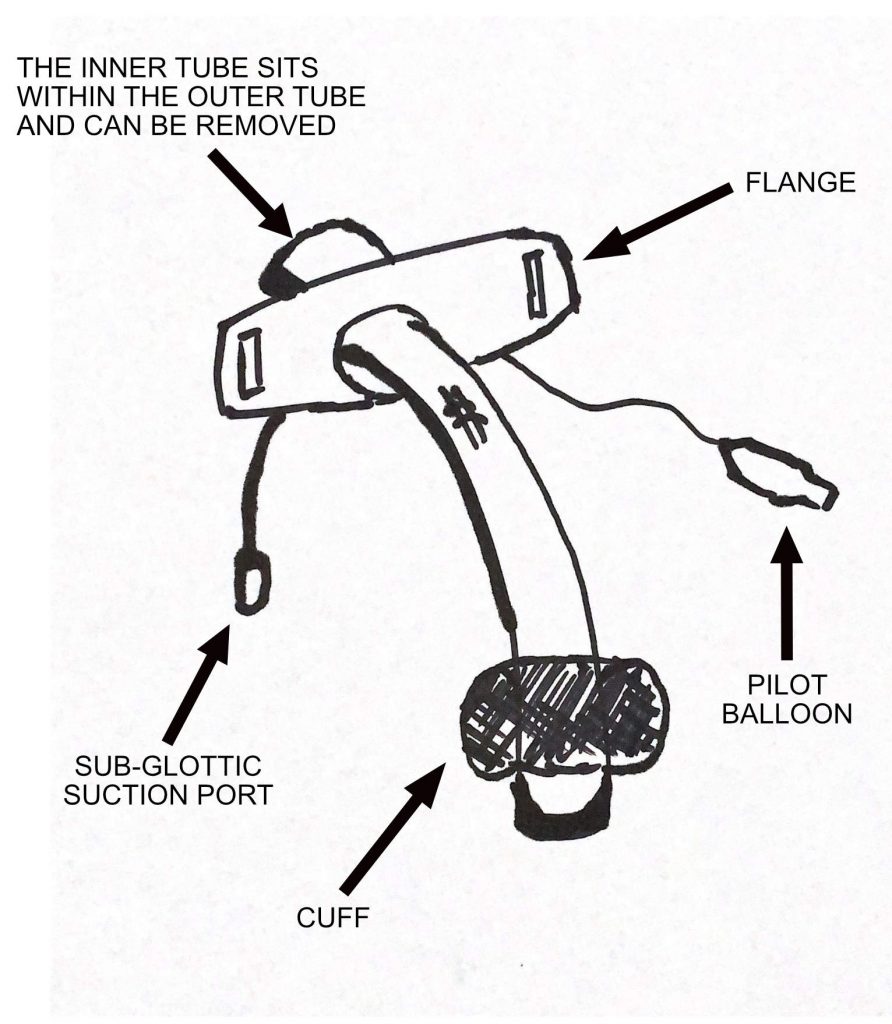

There are some important parts of the tracheostomy tube to be aware of:

- Tracheostomy – the opening created in the anterior wall of the trachea through which the tracheostomy tube can be passed

- The tracheostomy tube has a number of key parts

- The flange provides a method to secure the tracheostomy tube and prevent dislodgment

- The inflatable cuff allows for positive pressure ventilation and protection against aspiration

- The inner tube sits inside the outer tube and can be removed

- Sub-glottic suction port

- A tracheostomy tube may have an inflatable cuff and may be fenestrated

- “Passy-Muir” Valve or speaking valve – this is a valve that allows only inspiratory flow and not expiratory flow, thus forcing air around the tracheostomy and up through the vocal cords

Why?

- Prolonged respiratory wean, or prolonged need for mechanical ventilation

- Inability to protect airway or clear secretions

- Bypass an upper obstructed airway

When?

The largest trial for timing of tracheostomy was Tracman. This was a multi-centre, UK based trial comparing early (D4) vs. late (D10) tracheostomy. This showed no benefit (mortality) to early tracheostomy.

Several important issues around Tracman are:

- the trial did not include patients for any other reason than a respiratory wean (i.e. no neurological reasons were considered)

- only 45% in the late group received a tracheostomy

There is no significant evidence base to suggest early or late tracheostomy placement. Insertion should be patient specific and early tracheostomy could be considered in those whose clinical course is highly likely to need one (e.g. GBS, neurotrauma)

How?

Tracheostomies can be done either surgically or via a percutaneous method (known as a PDT, percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy).

Intensivists only perform the PDT approach. This will require at least two experienced, airway trained clinicians. One will do the procedure, and one will manage the airway and bronchoscope.

There are many techniques for doing a PDT – the most commonly seen would be the “Blue Rhino” technique which involves a single, tapered dilator.

Each operator will have their own little intricacies, but for a general overview the process is excellently summarised here (or on many YouTube videos):

Important contraindications include refusal, coagulopathy, severe haemodynamic instability or hypoxia, midline neck mass, local infection, difficult anatomy, and known difficult intubation.

Complications

Complications can be divided by their temporal occurence:

- Early: malposition, bleeding, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, tracheal injury, oesophageal injury, nerve injury, thyroid injury.

- Delayed: infection, ulceration, fistulae (tracheo-oesophageal or tracheo-innominate)

- Late: bleeding granuloma tissue, stenosis, persistent sinus, dysphonia.

Tracheostomy Emergencies

Respiratory Distress

There are best summarised by the National Tracheostomy Safety Project guidelines:

Some important considerations for a tracheostomy patient in respiratory distress:

- Do they have a patent upper airway? If so oxygenate and ventilate via mouth

- Remove any cap or speaking valve

- Is there an inner cannula? If so remove and replace as it might be blocked with secretions

- Can you pass a suction catheter through tracheostomy tube?

- If not then assume it is dislodged so don’t try positive pressure ventilation as if not in trachea this can lead to further injury

- If suction catheter does pass then (and ETCO2 present) then tracheostomy patent so can use

- If cuff exists then consider inflating to allow for positive pressure ventilation

- Investigate for causes of respiratory distress

Haemorrhage

The most life threatening cause of haemorrhage is a tracheo-innominate fistula. A smaller, sentinel bleed may precede a catastrophic bleed. Manage as per an ABC approach, correct coagulopathy and urgent consultations with ENT / Max Fax, Vascular +/- cardiothoracic surgeons +/- IR if suspected. Temporising measures include placing a finger in the sternal notch or tracheostomy stoma, and ensuring the tracheostomy cuff (if present) is maximally inflated.

Other causes of tracheostomy related bleeding include bleeding granulation tissue, infection, or erosion into adjacent smaller blood vessel.

If bleeding occurs early after placement then it may result from suction and manipulation of tracheostomy tube causing local trauma to the tracheal tree.

Weaning

There is no fixed approach to weaning. Some important parts of weaning include

- “Trache Shielding”: the process by which the patient is not attached to the ventilator and has an oxygen mask over the tracheostomy tube.

- Signs that the patient needs to return back to the ventilator include tachypnoea, hypoxia and hypercarbia

- Progressive increments of time with cuff down +/- PMV

- The tracheostomy may need to be “down sized” to a smaller tracheostomy tube if it fits too tightly in the trachea. This is often noted when a PMV (or tracheostomy occluded) is attached and air cannot exit the tracheostomy tube or bypass it and exit via the mouth. Downsizing allows more room for air to bypass.

- The patient cannot be connected to the ventilator with the cuff down.

- “Capping”: Some units will cap the tracheostomy when the patient has spent a set period of time (usually >24 hours) with the cuff down. This “blocks off” the tracheostomy so all the air has to pass through the mouth.

- Its an MDT approach with physio, speech and language +/- ENT usually involved

- For weaning to be successful you need

- Resolution of reason for tracheostomy

- Patent upper airway with adequate airway protective reflexes

- Awake, alert and co-operative patient

- No need for mechanical ventilation

- Secretion load manageable (good cough)

References and Further Reading

National Tracheostomy Safety Project

BJA Education: Tracheostomy Management

BJA Education: Update on Management

Author: George Walker